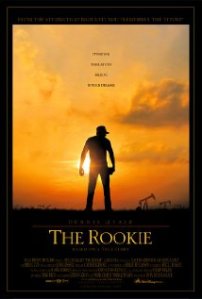

Jim Morris attracted a fair amount of attention when he made his major league baseball debut with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 1999, and even more when the story of his life became a movie starring Dennis Quaid (“The Rookie”) in 2002. A promising young pitcher who was drafted out of junior college as a 19-year-old, Morris gave up on his playing career in 1989 because of arm problems, went to college (and played football, leading the NCAA’s Division II in punting and earning Little All-America honors in 1992) and was a high school teacher and coach before his players encouraged him to give pro ball another shot — at age 35. The Devil Rays, in their second year of existence, signed him to a minor league contract and brought him to the big leagues that September.

Jim Morris attracted a fair amount of attention when he made his major league baseball debut with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 1999, and even more when the story of his life became a movie starring Dennis Quaid (“The Rookie”) in 2002. A promising young pitcher who was drafted out of junior college as a 19-year-old, Morris gave up on his playing career in 1989 because of arm problems, went to college (and played football, leading the NCAA’s Division II in punting and earning Little All-America honors in 1992) and was a high school teacher and coach before his players encouraged him to give pro ball another shot — at age 35. The Devil Rays, in their second year of existence, signed him to a minor league contract and brought him to the big leagues that September.

On his website Morris refers to himself as “The Oldest Rookie” (although he has nothing on Quaid, who was 47 when he portrayed Morris in the movie). No doubt Morris put the words in quotation marks because he knows he wasn’t actually the oldest man to reach the major leagues; in fact, an older rookie reached the majors the year after Morris. Using Baseball-Reference.com’s Play Index feature, I find 27 players who were at least 36 years old when they played in their first major league game, going back to 1916. The complete list is at the end of this post.

Of those players, five (Satchel Paige, Quincy Trouppe, Pat Scantlebury, Bob Thurman and Buzz Clarkson) were delayed in beginning their careers in Organized Baseball because they were black; six, all pitchers, came to the American majors from Japan (Ken Takahashi, Masumi Kuwata, Chang-Yong Lim, Keiichi Yabu, Satoru Komiyama and Takashi Saito); and seven others made their debut during World War II, when most younger players were in the service (Chuck Hostetler, Joe Berry, Lee Riley, Otho Nitcholas, Ernie Rudolph, Joe Vitelli and Buck Fausett).

Here are the stories of these oldest rookies (well, all except the ones who came from Japan). One thing almost all of them have in common: they passed themselves off as younger than they really were. Another thing almost all of them have in common: they were very good players, somewhere, for a long time.

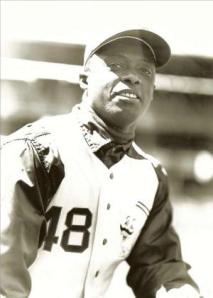

Satchel Paige is the only player on this list in the Baseball Hall of Fame, enshrined largely for his achievements in the Negro Leagues and as a barnstormer before he reached the majors once the de facto ban on black players was lifted with the arrival of Jackie Robinson. Paige liked to stir up controversy about his birth date, and his age was always a matter of conjecture during his playing career, but it’s no longer questioned that he was born July 7, 1906, meaning he was two days past his 42nd birthday when he made his debut with the Cleveland Indians. He pitched regularly in the majors past his 47th birthday, was still an outstanding pitcher in the minors the year he turned 52, and pitched three shutout innings in a regular season major league game when he was 59.

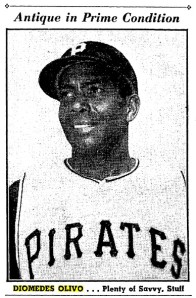

Diomedes Olivo was older than he let on when he reached the major leagues in 1960. During his playing career he listed his birth date as Jan. 22, 1920; his obituary in The Sporting News after his death in 1977 said he had been a 40-year-old rookie. But it’s now believed he was born Jan. 22, 1919, making him 41 when he played in his first game for the Pittsburgh Pirates. A native of the Dominican Republic, Olivo didn’t start playing in the Cuban winter league until 1947 and didn’t begin playing in Organized Baseball until he was 36. According to a story by Harry Keck in The Sporting News of May 23, 1962, “Because of the language barrier, he preferred to play in Latin American countries and also had a horror of fighting his way up through the Class C and D leagues in this country.”

Diomedes Olivo was older than he let on when he reached the major leagues in 1960. During his playing career he listed his birth date as Jan. 22, 1920; his obituary in The Sporting News after his death in 1977 said he had been a 40-year-old rookie. But it’s now believed he was born Jan. 22, 1919, making him 41 when he played in his first game for the Pittsburgh Pirates. A native of the Dominican Republic, Olivo didn’t start playing in the Cuban winter league until 1947 and didn’t begin playing in Organized Baseball until he was 36. According to a story by Harry Keck in The Sporting News of May 23, 1962, “Because of the language barrier, he preferred to play in Latin American countries and also had a horror of fighting his way up through the Class C and D leagues in this country.”

When Olivo did break into Organized Ball, it was with the Havana team of the International League, and after one season with them he spent the next four summers in Mexico, where he also played outfield and pinch-hit. The Pirates signed him in April 1960, after he had won 21 games in Mexico in 1959, and after a good season with the Bucs’ Columbus farm club in the International League Olivo made his debut for the Pirates in September. He was back at Columbus in 1961 and was named the IL’s Pitcher of the Year at age 42, then returned to Pittsburgh in ’62 and had a solid year pitching out of the bullpen at age 43.

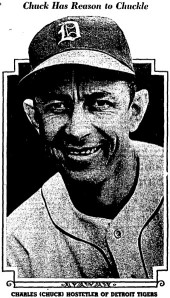

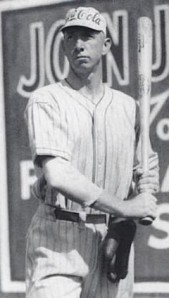

Chuck Hostetler, the oldest man ever to bat in his first major league game (and the oldest man to get a hit in his debut), was also older than he claimed to be when he arrived in the big leagues. “Hustling Chuck Hostetler, Rookie at 38” cries the page-width headline in the May 18, 1944, Sporting News, but although Chuck had given his birth date as Sept. 22, 1905 (it’s listed as Sept. 2, 1905 in the 1945 Street & Smith’s, likely just a typo), he was actually born Sept. 22, 1903, making him 40 when he earned a spot on the Detroit Tigers’ roster in spring training 1944. “In these days, anybody who can hit is mighty welcome on a ball club,” Tigers manager Steve O’Neill told Fred Lieb for that Sporting News article, “and Chuck really can hit.”

Chuck Hostetler, the oldest man ever to bat in his first major league game (and the oldest man to get a hit in his debut), was also older than he claimed to be when he arrived in the big leagues. “Hustling Chuck Hostetler, Rookie at 38” cries the page-width headline in the May 18, 1944, Sporting News, but although Chuck had given his birth date as Sept. 22, 1905 (it’s listed as Sept. 2, 1905 in the 1945 Street & Smith’s, likely just a typo), he was actually born Sept. 22, 1903, making him 40 when he earned a spot on the Detroit Tigers’ roster in spring training 1944. “In these days, anybody who can hit is mighty welcome on a ball club,” Tigers manager Steve O’Neill told Fred Lieb for that Sporting News article, “and Chuck really can hit.”

Hostetler had a .307 career average in ten minor league seasons (the first of which came when he was 25 but believed to be 23), then after the 1937 season he took a job at the ship canal in Baytown, Texas, to support his family, and turned to playing semi-pro ball. He later moved to Wichita and was a member of teams that took third place in the 1942 and 1943 semi-pro national tournaments.

After the 1943 season, Tigers general manager Jack Zeller was desperate for outfielders because of players called to military service, and among the people he queried searching for replacements was Red Phillips, a Tiger pitcher in the mid-’30s who was doing some umpiring around Wichita. Phillips recommended Hostetler, and once Zeller talked to Chuck and received assurances he was still in good physical condition (“I’m one of those wiry fellows who doesn’t put on much weight,” Hostetler reportedly told Zeller), Zeller invited Hostetler to spring training.

Hostetler hit .350 in exhibition games and was second on the team in runs batted in, earning a spot on the regular season roster. He finished the season with a .298 batting average in 90 games, 65 of which he started in the outfield, and was named to The Sporting News’ all-rookie team. He also spent the entire 1945 season on the Detroit roster but did not play as much or as well, hitting just .159 in 44 at-bats and starting only four games. But Hostetler was used as a pinch-hitter three times in the 1945 World Series against the Cubs. In his final appearance, in Game 6, he reached base on an error and later tried to score from second on a single but fell down between third and home and was tagged out. The Tigers went on to lose that game but won Game 7 to take the championship. (A story by Furman Bisher in The Sporting News of Oct. 20, 1973, said Hostetler fell down trying to score “the winning run in one of the games,” but the Tigers actually trailed 5-1 at the time, although they rallied to tie the score before losing in extra innings.) With the war over in 1946, Hostetler left Organized Ball. (ADDED 9/9/16: Marc Lancaster has written a much more thorough biography of Hostetler for the Society for American Baseball Research’s Baseball Biography Project.)

Hostetler was, at the time of his debut, the oldest man to appear in his first major league game. The man who held that distinction before him was Alex “Red” McColl, who won 332 games in his minor league career, ranking sixth on the all-time list, the last of which came when he was a 47-year-old player-manager in the Class D Pennsylvania State Association. And he sat out one full season (1926, when he was “just” 32) as voluntarily retired, apparently due to an injury. But in 1933 — 18 years after he had begun his professional career — the Washington Senators brought the then-39-year-old McColl to the majors, and on Sept. 6 he pitched a four-hitter to beat the White Sox, 3-1. The Senators won the American League pennant and McColl pitched two scoreless innings in relief in Game 2 of the World Series. (It’s interesting that Paige and McColl pitched in the World Series in their debut year, Hostetler played in the World Series the year after and his team was in the race until the final day in his rookie year, and Olivo pitched for a team that won the World Series weeks after he debuted, although he was not eligible to play in it.)

I haven’t come across anything that explains why the Senators, in a pennant race, turned to a 39-year-old who not only had no major league experience but hadn’t even pitched at the highest minor league level for 11 years. (McColl wasn’t trying to fib about his age; The Sporting News reported him to be 39 after he reached the majors.) McColl spent most of the 1934 season with the Senators and did not play in the majors after that, but he spent another seven years (and won another 85 games) in the minors.

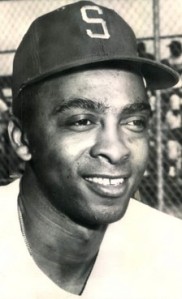

Quincy Trouppe (his birth name was spelled Troupe and that’s how it typically appeared in his playing days, he said he added the second “p” after playing in Mexico) is the oldest man to play a position other than pitcher in his major league debut. (Chuck Hostetler was a pinch-hitter in his first game.) Although he certainly didn’t own up to his age when he was with the Cleveland Indians in 1952…here’s what Harry Jones wrote in the Cleveland Plain Dealer of Feb. 28, 1952:

Quincy Trouppe (his birth name was spelled Troupe and that’s how it typically appeared in his playing days, he said he added the second “p” after playing in Mexico) is the oldest man to play a position other than pitcher in his major league debut. (Chuck Hostetler was a pinch-hitter in his first game.) Although he certainly didn’t own up to his age when he was with the Cleveland Indians in 1952…here’s what Harry Jones wrote in the Cleveland Plain Dealer of Feb. 28, 1952:

Quincy Troupe…denies the report he attended Satchel Paige’s christening.

But when asked to give his age today, right after he had checked into the Tribe’s training camp, the big fellow studied the pocket in his over-sized receiver’s mitt before answering.

“I’m 30,” he said at last. “That is, I’ll be 30 on my next birthday. Actually, I’m 29.”

An article in the Boston Daily Record after Troupe’s first regular season start said he was 35. Actually, Troupe had turned 39 the previous Christmas Day.

Trouppe had played in the Negro Leagues as a young man, then was a teammate of Satchel Paige’s on the integrated Bismarck (N.D.) Churchills team that won the first semi-pro national championship in 1935. Trouppe had also played in Mexico and played and managed in winter ball before joining the Indians, returning to Cleveland where he had been a player-manager for the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League from 1945-47.

Trouppe actually signed with Indianapolis of the American Association, which had a working agreement with Cleveland, but he earned a spot on the major league team with a strong spring training (“for the time being,” manager Al Lopez told reporters). Trouppe had his tonsils removed on April 21, just a week into the regular season, and wasn’t able to eat solid foods for a week after that.

The Indians’ regular catcher Jim Hegan sprained an ankle on April 30, and Trouppe made his debut as Hegan’s replacement in the game in which he was hurt. But in Hegan’s absence Lopez turned to 37-year-old Birdie Tebbetts as his primary catcher, because of Tebbetts’ knowledge of American League hitters from his 13 years in the league. Trouppe started just two games, getting his only major league hit in the second one, before being sent to Indianapolis when major league rosters had to be trimmed from 28 players to 25 in late May. The Associated Press item about Trouppe’s demotion said he was 29 years old. At the end of the season Trouppe was given $200 by his teammates as his share of the World Series earnings for the Indians’ second-place finish (a full share was worth $1,066.35).

After the 1952 season Troupe ended his playing career and became a scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, who at that time still hadn’t had a black player in the majors. “One of the first things Mr. [August] Busch told us when he [bought] the club was that he wanted good ball players regardless of race, color or creed,” Cardinals chief scout Joe Mathes told The Sporting News in January 1954. “With the help of Troupe, we’ve now got 13 colored boys among our 141 professional rookies.” But Trouppe was reportedly upset that his recommendations of future Hall of Famers Ernie Banks and Roberto Clemente were ignored. [ADDED 3/25/16: Jay Hurd tells Trouppe’s story as part of the SABR Bio Project.]

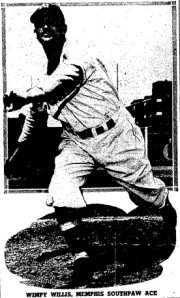

Les “Wimpy” Willis, a left-handed screwball pitcher, took a very unusual path to reach the major leagues at age 39. Although, like so many others on this list, he had fudged his age; the 1947 Street & Smith’s gives his birth date as Jan. 17, 1912, when he was actually born four years before that. Just 5’9″ and 195 pounds, Willis was described as “rotund,” “roly-poly,” “quite chubby” and “the portly portsider” — and I found all those without looking that hard. (“Wide Wimpy” was a nickname that appeared in print.)

Les “Wimpy” Willis, a left-handed screwball pitcher, took a very unusual path to reach the major leagues at age 39. Although, like so many others on this list, he had fudged his age; the 1947 Street & Smith’s gives his birth date as Jan. 17, 1912, when he was actually born four years before that. Just 5’9″ and 195 pounds, Willis was described as “rotund,” “roly-poly,” “quite chubby” and “the portly portsider” — and I found all those without looking that hard. (“Wide Wimpy” was a nickname that appeared in print.)

I’m not sure why, but Willis didn’t begin his professional career until he was 24 years old (a Sporting News story of Aug. 28, 1946, confirms 1932 was his first year in the minors), and then he posted a 7-29 record in his first three seasons. At that point he rolled out three straight 20-win seasons at the Class C level, earning a promotion to Louisville of the American Association…where he lost 21 games in 1938. He bounced back to win 18 games for Memphis of the Southern Association in 1940 but fared worse the next two years, then missed three seasons (1943-45) entirely — not because he was fighting World War II but because his arm was bad.

It was tough to get a job playing baseball in 1946, with all the ballplayers back from the service, but somehow Willis not only caught on at Memphis, he had his best season, going 18-7 with a 2.37 ERA, leading the league with six shutouts, pitching 37-2/3 consecutive scoreless innings and throwing a no-hitter. The Cleveland Indians drafted him that winter and he spent the entire 1947 season in the big leagues. He didn’t pitch well and he didn’t win a game, although he did make two starts. He didn’t play pro ball after that season, and he later became mayor of his longtime home, Jasper, Texas.

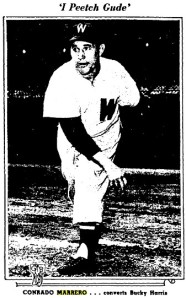

“Connie” Marrero — who, as this was written, is the oldest former major leaguer at age 102 — deserves a much better telling of his life’s tale than I’m prepared to do here. (UPDATE 4/24/14: Marrero died April 23, 2014, two days before his 103rd birthday.) Fortunately, Peter Bjarkman has done that as part of the Society for American Baseball Research Baseball Biography Project.

“Connie” Marrero — who, as this was written, is the oldest former major leaguer at age 102 — deserves a much better telling of his life’s tale than I’m prepared to do here. (UPDATE 4/24/14: Marrero died April 23, 2014, two days before his 103rd birthday.) Fortunately, Peter Bjarkman has done that as part of the Society for American Baseball Research Baseball Biography Project.

Marrero’s age was a constant topic of discussion during his five seasons with the Washington Senators. Morris Siegel wrote this in The Sporting News of May 9, 1951:

Marrero’s age has been estimated from 30 to 45. He’s mum on that subject, pointing only to the number on the back of his uniform when asked how old he is.

The number? 22.

In 1950, his rookie year with the Senators, Street & Smith’s listed his birth date as May 1, 1917. But he was actually born in Havana on April 25, 1911, making him four days short of his 39th birthday when he first appeared in a regular season game. As evidence that the estimates of Marrero’s age varied, a story in The Sporting News in June 1952 said he was 43, when that year’s Street & Smith’s said he was 35 and he was actually 41. To further emphasize the confusion, a Sporting News story in January 1955 said Marrero would be “43 in May,” which would finally have made him the age he was reported to be in the same publication three years earlier. And it was still wrong.

Marrero — somewhere between 5’5″ and 5’7″ in his playing days — broke into Organized Baseball in 1947 with the Havana team of the Florida International League and won 70 games over three seasons for that squad before joining the Senators. He was named to the All-Star team in 1951, got a tenth-place vote for Most Valuable Player in 1952 and had a good year in 1953 before his final major league season in 1954 at age 43. He pitched for Havana’s team in the Class AAA International League until 1957.

Pat Scantlebury, a native of Panama, is the oldest player to be in the starting lineup in his first major league game, but no one knew it at the time because he had shaved eight years off his age. An Associated Press story when Scantlebury was purchased by the Reds in October1955 said he was 29; the 1956 Street & Smith’s lists his birth date as Nov. 11, 1925. But he was actually born on Nov. 11, 1917, making him 38 when he first took the hill for Cincinnati. His major league career numbers (6 games with an 0-1 record and a 6.62 ERA) are misleading, as he had a notable baseball career over more than 25 years and is a member of the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame (he was inducted the same year as Diomedes Olivo).

Scantlebury came to the U.S. in 1944 to pitch for the New York Cubans of the Negro National League. He and Luis Tiant Sr. (father of the major league star) pitched the Cubans to the 1947 NNL pennant, and Scantlebury was the winning pitcher (in relief of Tiant) in the deciding game of the Negro World Series against Cleveland. Future major league star Minnie Minoso was the Cubans’ third baseman. Scantlebury also pitched in the Negro Leagues All-Star Game in 1949 and ’50.

In 1950 Scantlebury was named most valuable player of the National Baseball Congress’ national tournament for non-professional teams, allowing just four runs in 36-1/3 innings. His Fort Wayne Capeharts came through the losers’ bracket of the double-elimination tournament to meet unbeaten Elk City, Oklahoma, in the finals, with the Capeharts needing to win consecutive games to take the title. In the first game Scantlebury pitched a 12-inning four-hit shutout, striking out 12, and doubled in the game’s only run. The next night he came on in relief to face the tying run with two on and none out in the top of the ninth and retired all three batters he faced, striking out two, to nail down the win. From Wichita, the site of the tournament, the Capeharts flew to Tokyo and won the “First Official Inter-Hemisphere Playoff,” taking four of five games from a Japanese team in front of huge crowds. Scantlebury won the first and last games games, allowing just two runs in 18 innings, and was named best pitcher of the tournament.

Scantlebury had plenty of other experience before going into Organized Baseball, playing in his own country, in Caribbean winter leagues, in Mexico in 1951, and on Roy Campanella’s barnstorming teams that toured the U.S. after the 1951 and ’52 seasons. Then in 1953 Scantlebury joined Texarkana of the Class B Big State League and was a sensation, winning his first seven decisions and leading the league with 24 wins and 177 strikeouts while hitting five home runs (he was also used as a pinch-hitter). He won 20 games the next year, 18 for a Dallas team that finished a distant last in the Class AA Texas League and two after he was purchased by Havana of the Class AAA International League.

That was enough to earn Scantlebury a trip to Cincinnati’s training camp in 1955, but he had a bad arm and didn’t show much. Sent back to Havana, he was used as a starter and in relief and posted a 13-9 record with a 1.90 ERA. The Reds purchased his contract after the season and they had high hopes for him for 1956; Scantlebury fueled those hopes with an excellent spring training. But when the regular season came he didn’t get much of a chance.

That was enough to earn Scantlebury a trip to Cincinnati’s training camp in 1955, but he had a bad arm and didn’t show much. Sent back to Havana, he was used as a starter and in relief and posted a 13-9 record with a 1.90 ERA. The Reds purchased his contract after the season and they had high hopes for him for 1956; Scantlebury fueled those hopes with an excellent spring training. But when the regular season came he didn’t get much of a chance.

Scantlebury started the second game of the season, against St. Louis, and was lifted after giving up a leadoff home run in the sixth inning, the fourth run he had allowed in the game. Five days later he started against the Cardinals again and was removed for a pinch-hitter after allowing three runs in four innings. That would be his final major league start. He made two more relief appearances before being sent back to Havana when the Reds had to reduce their roster to 25 players in mid-May, then was recalled in late July and made two more relief appearances before being sent to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League as compensation when the Reds acquired pitcher Larry Jansen from the Rainiers.

Cincinnati’s manager was Birdie Tebbetts…the same fellow who beat out Quincy Trouppe for the backup catching job in Cleveland in 1952. Tebbetts apparently wasn’t buying the party line that Scantlebury was 30, as evidenced by this exchange reported by W. Rollo Wilson of the Pittsburgh Courier in The Sporting News of June 26, 1956, after Scantlebury had been sent to Havana. Quoting Tebbetts, Wilson wrote, “‘He [Scantlebury] might still be able to help us in the stretch even if he is old and will never be any better than he is now.’ (Tebbetts glared at me, silently daring me to challenge his statement as to the Panamanian’s age.)”

Scantlebury continued to pitch in the high minors, and pitch well, through the 1961 season, when he was 43 years old. In nine years of Organized Baseball he won 114 games, despite not starting until he was 35. He made his home in New Jersey and continued to play semi-pro ball for some time after he left Organized Ball and later coached until contracting Parkinson’s disease a few years before his death in 1991. [ADDED 3/24/17: Graham Womack has more on Scantlebury here.]

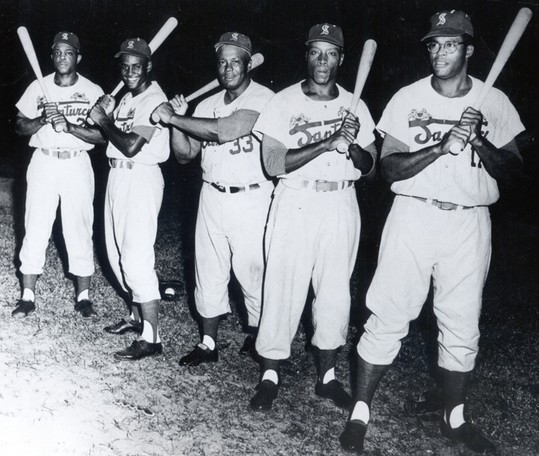

Bob Thurman is another former Negro Leaguer who shaved some years off his age when he entered Organized Baseball. During his major league career Street & Smith’s always listed his birth date as May 14, 1923, but he was actually born six years before that and thus was a month away from his 38th birthday when he made his first appearance for the Reds in 1955. (I have a 1951 San Francisco Seals roster that shows his birth year as 1922.) Thurman played four years in the minors, then left Organized Baseball to play in the Dominican Republic in the summers of 1953 and ’54. In the winter of 1954-55 Thurman was part of an outfield with Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente on one of the greatest winter league teams of all time in Santurce, Puerto Rico, and that led to his signing with the Reds.

Bob Thurman is another former Negro Leaguer who shaved some years off his age when he entered Organized Baseball. During his major league career Street & Smith’s always listed his birth date as May 14, 1923, but he was actually born six years before that and thus was a month away from his 38th birthday when he made his first appearance for the Reds in 1955. (I have a 1951 San Francisco Seals roster that shows his birth year as 1922.) Thurman played four years in the minors, then left Organized Baseball to play in the Dominican Republic in the summers of 1953 and ’54. In the winter of 1954-55 Thurman was part of an outfield with Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente on one of the greatest winter league teams of all time in Santurce, Puerto Rico, and that led to his signing with the Reds.

While he was only a part-time player in the majors, Thurman hit 35 home runs in 663 at-bats…not bad for a man who didn’t get the first of those at-bats until he was almost 38. He is also the all-time leader in home runs in the Puerto Rican Winter League and was the league MVP in 1950-51; he was part of the first class elected to the Puerto Rican Baseball Hall of Fame, along with Clemente and Orlando Cepeda, in 1991. Rick Swaine does a fine job telling Thurman’s story as part of the SABR Bio Project.

Add Joe Berry to the list of players who portrayed himself as younger than he was. Although he may not have been fooling anybody…Jim Coleman of the Toronto Globe and Mail wrote in The Sporting News in 1946, “Joe claims to be 37 years of age, but, actually, he is considerably older than that.” Heck, he was older than that in 1944, when Red Smith, writing in The Sporting News, gave Berry’s birth date as Dec. 16, 1905, making him 38. Street & Smith’s that year (and every year of his major league career) reported his birth date as Dec. 16, 1907, but it was actually Dec. 16, 1904.

Berry’s build would best be described as “slight.” While he was typically listed as weighing 145 pounds, Coleman wrote “he weighs only 135 pounds and looks as harmless as a dead moth.” His longtime nickname was “Jittery Joe” — “about the most inept misnomer a ball player ever wore,” Smith wrote. “It was inspired by his hitchy-itchy pitching motion. If there ever was a day when he experienced a single nervous jitter, the memory of it is buried somewhere deep in his dark and practically bottomless past.”

Berry began his professional career in 1927. He had three 20-win seasons in the low minors and later spent six years with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. When the last of those seasons didn’t go so well (6-10, 5.26 ERA), the Angels sold him to Tulsa of the Texas League, where he had a superb year in 1942 with an 18-8 record, a 1.88 ERA and a no-hitter. The Cubs purchased him in September, and the then-37-year-old made two ineffective relief appearances.

He went to spring training with the Cubs in 1943 and survived until the last day, when he was sent to Milwaukee of the American Association and had another very good season (18-10, 2.78). The Philadelphia A’s purchased his contract that winter and Berry went on to become the American League’s top relief pitcher as a 39-year-old rookie in 1944 (10 wins, a 1.94 ERA and a league-leading 12 saves, figured retroactively), followed by another excellent performance in ’45. He pitched one more year in the majors followed by two in the minors, then after a year off came back for two more seasons as a player-manager, ending his playing career at age 46 with 269 career professional wins.

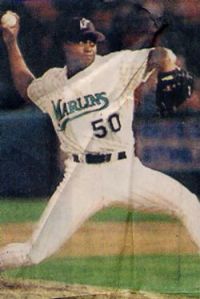

Joe Strong was the player who came to the majors the year after Jim Morris. It was May 2000 — 16 years after he was drafted by the Oakland A’s out of the University of California, Riverside — when Strong made his first appearance for the Florida Marlins at age 37. His road to the majors may have been the most unusual of all.

Released by the A’s in January 1987, he sat out that entire season with an injury before returning to play with Reno, an independent team in the Class A California League, in 1988-89. Reno released him, after which he spent three years in Taiwan (1990-92) before returning to the minors with the Padres; was let go after the 1993 season and signed with another independent California League team for 1994; spent time as a “replacement player” for the Cubs during the major league players’ strike in the spring of 1995, then spent that season playing for a Canadian team in the independent Western League; had shoulder surgery and spent TWO years driving a forklift at a Sears warehouse before playing in Korea in 1998.

In 1999 — the same year Tampa Bay signed the 35-year-old Morris to a minor league contract — the Devil Rays also took a chance on the 36-year-old Strong, who threw hard but got lousy results. In July the Devil Rays loaned him to a team in the Mexican League, and after he was granted free agency at the end of the season he stayed in Mexico to play winter ball. That’s when he caught a break: one of the scouts who saw him there was Tim Schmidt, who was a first-year assistant coach at UC Riverside in Strong’s last season there, 1984. Here’s how Mike Berardino told the story in the Orlando Sentinel after Strong reached the big leagues in May 2000:

When he asked Strong how he was throwing in a brief pregame chat, Schmidt only was making conversation.

“Schmitty, I’m throwing 91-95 mph,” said Strong, then the top reliever for the Obregon Yaquis.

Schmidt rolled his eyes. “Come on, Joe,” he said. “I coached you.”

A few hours later, Strong got into the game and backed up his boast.

“The first pitch was 94 mph,” Schmidt said. “Next one was 95, then 96. I’m the only scout in the stands, and I’m sitting there thinking, ‘God almighty.'”

Schmidt talked his bosses into letting him sign a pitcher who had just turned 37. Strong started the 2000 season (in a foreign country, of course) with the Marlins’ Class AAA farm club at Calgary. Then in May, when Marlins pitcher Ricky Bones had to go on the disabled list when he strained his back watching TV in the clubhouse (seriously, that’s what the Miami Herald reported), Strong got the call he had long hoped for to come to the major leagues, and he didn’t allow a run in his first four appearances. He drew considerable national media attention as the oldest rookie since Diomedes Olivo. His manager, John Boles, wondering where a 37-year-old who threw 95 miles an hour came from, compared him to Sidd Finch.

“If I had a dollar for every time someone told me I was too old, I’d be a rich man and I wouldn’t be here,” Strong said after joining the Marlins. “But that just adds fuel to the fire.”

Strong pitched in 19 games during the season; three ugly appearances left his season ERA at a gruesome 7.32, but he did get a win and a save. He made five more appearances with the Marlins early in the 2001 season, and while he didn’t play in the majors after that, he kept pitching — in the minors, in independent leagues, in Mexico — until he was 41. (Thanks to SABR members Ed Washuta, Andy McCue and Rod Nelson for their help in confirming the chronology of Strong’s career.)

Leon “Lee” Riley may have been almost as unlikely to reach the major leagues as Strong. In 1942 he hit .204 in the Class B Interstate League. In 1943 he sat out the season in a salary dispute. In 1944 he started the season with the Phillies as a 37-year-old outfielder. Well, there was a war on, so that helped.

Riley had a long and successful minor league career, including four years as a player/manager before joining the Phillies, but most of it was in the lower minors. He had won two batting championships and a home run title, all for teams he also managed (he would win another home run crown as a player-manager after leaving the Phils). He would finish his minor league career with 2,418 hits and a .314 batting average plus 248 homers (his Baseball-Reference.com stats are missing 23 hits and two homers he hit in 1927, according to The Minor League Register from Baseball America).

In his month in the major leagues Riley played four games, starting two, and got one hit before being sent back to the minors. He resumed his player-manager duties in 1945 and managed another eight seasons in the Phillies’ farm system (Baseball-Reference.com doesn’t show that he managed Wilmington in the Interstate League in 1952). In 1952 the Phils decided to replace major league manager Eddie Sawyer at midseason; Riley reportedly thought he had a chance to get the job, but it went to longtime big league skipper Steve O’Neill. The Phils dropped Riley as a manager at the end of that season, and his days in Organized Baseball were over.

According to his obituary in the Schenectady (N.Y.) Gazette, Riley operated a variety store after his baseball career ended and “was associated with” Bishop Gibbons High School in Schenectady from 1964 until his death from a heart attack in 1970. An article in Sports Illustrated in 1985 said Riley had suffered “business setbacks” and had been a janitor at Bishop Gibbons; his obituary doesn’t mention any custodial duties but says he was the school’s baseball coach in 1969 and ’70.

Lee Riley had two sons who played professional sports. Lee Riley Jr. spent five seasons in the NFL and two in the AFL from 1955-62. The youngest of Lee Sr.’s six children was a high school quarterback who turned down a chance to play for Bear Bryant at the University of Alabama to pursue a career in basketball. That turned out pretty well for Pat Riley, who won five NBA championships as coach of the Lakers and Heat to earn a spot in the Basketball Hall of Fame. (ADDED 9/9/16: Mel Marmer has more about Riley in his SABR Bio Project biography.)

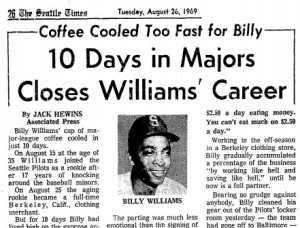

Billy Williams (not the Hall of Famer who played at roughly the same time) was the oldest man ever to be used as a pinch-runner in his major league debut — and he was thrown out trying to score the tying run from third on a two-out safety squeeze bunt. Home plate umpire Frank Umont said Williams missed the plate. “He was so intent on kicking the ball away from [Baltimore catcher Elrod] Hendricks he missed the plate entirely,” Umont said after the game. “Yeah, I heard Williams was making his first big league appearance after something like 17 years in the minors. It’s tough. He had a chance to be a hero. But he blew it.”

Williams’ side of the story: “I knew I was safe. I was. And listen, Hendricks never did make the tag. He has to tag me out on that play [it was not a force-out situation]; he can’t just touch the plate or wait for me to leave the basepath. He has to make the tag, and he STILL hasn’t tagged me.”

Such was life with the 1969 Seattle Pilots.

Umont actually underestimated the length of Williams’ apprenticeship; 1969 was his 18th season of minor league baseball. Williams finally did score a run before his 10-day major league career ended, but he never did get a hit.

Williams’ age has changed over the years. I don’t have any publications from his playing days that include his birth date, but when he was called up to the Pilots in mid-August 1969 he was reported to be 35. Later his birth date was given as June 13, 1933, which would have made him 36 when he reached the majors. But after he died in June 2013, his obituary listed his birth date as June 13, 1932, which would have made him 37 when he debuted. Of course, his obituary also says he was 39 when he played for the Pilots, so there’s at least one error in the obituary. (By the way, it was the news of Williams’ death that triggered the idea for this post.)

Billy Williams began his professional baseball career in 1952 as the first African-American player in the Class D Mountain States League, a six-team loop with towns in Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky. In 1954 he began a 15-year career in the Cleveland organization, not reaching the Class A level until 1960. But from 1961-69 he was a regular in the Pacific Coast League, never a star but always good enough to play, and he spent some time as a player-coach in Portland.

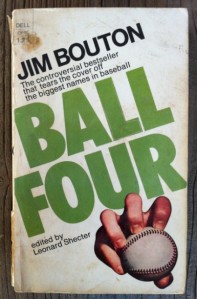

The Pilots acquired him early in the 1968 season, the year before the team actually hit the field, and assigned him to the PCL’s Seattle Angels; there he was a teammate of pitcher and future author Jim Bouton, who had also signed early with the Pilots. Williams was hitting .283 with seven homers and 79 RBI (his highest RBI total in nine years) for Vancouver in ’69 when he got the call to the big leagues.

And yes, Williams does appear in Bouton’s classic diary of the 1969 season, “Ball Four.” “He’s a good-hitting outfielder,” Bouton wrote. “He should have had a better shot but I think he’s one of those Negroes who wasn’t quite good enough to be a star and wound up a good minor leaguer….There are a lot of Negro stars in the game. There aren’t too many average Negro players. The obvious conclusion is that there is some kind of quota system.” Later in the book Bouton reveals Williams was being paid $1,300 a month at Vancouver (paid only during the five-month season); when he was promoted to the Pilots he got a raise to the major league minimum, prorated at $1,666 a month.

While Williams’ stay in the big leagues was only ten days, he appreciated the big league meal money while he got it. “You can do an awful lot of eating on $15 a day,” he said before he departed, looking back on the $2.50 a day he had received in the Northern League in the ’50s. He was nothing but classy in his departure: “I owe everything to baseball. It took me away from the Virginia coal mines and gave me an appreciation of my country.”

An Associated Press story in the Seattle Times on Aug. 26, 1969, after Billy Williams was released by the Pilots

Billy Williams never played professional baseball after leaving the Pilots, finishing his minor league career with 2,171 hits. Rather than returning to Vancouver for the final days of the minor league season, he went home to California and the clothing store he managed in Berkeley. He had worked there for a number of offseasons and by “working like hell and saving like hell” he bought into the business and was a full partner by the time he played for the Pilots.

And he wasn’t anxious to go back to baseball. “After I got let go [by the Pilots], I got real frustrated with my whole situation in terms of baseball,” Williams told a reporter in 2005. “So I went into the private sector. I owned a couple of clothing stores in Oakland.”

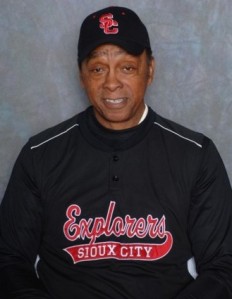

But Williams would return to the game. In 1987 he took a job scouting for the Indians, then in 1988 managed their Gulf Coast League team. The next year he was a coach for the Indians’ Class AA affiliate at Canton-Akron, and then he was back in a major league uniform in 1990 and ’91 as a “coaching assistant,” working with players in pregame sessions. But because the Indians had five other coaches, he couldn’t be in uniform during games, so he kept batting and pitching charts from the stands. From 1992-99 Williams was a minor league coach in the Cleveland organization, then in 2000 he joined the coaching staff of the Sioux Falls Canaries of the independent Northern League. After five years there he moved to the Sioux City Explorers of the same league (and later the independent American Association) and spent five seasons there, including a brief stint as interim manager at the end of the 2005 season. His last year in uniform was 2009, the summer he turned 77.

Thanks to SABR members Bob Kerler and Andy McCue for their help in providing information about Williams.

Jim “Buzz” Clarkson (also sometimes referred to by his middle name, Buster, or Bus) is another Negro Leagues player who deducted a few years (in his case, three) from his age when he joined Organized Baseball. Clarkson had also played in Mexico and Canada (and missed three years for military service in World War II, his gravestone says he was a sergeant in the Army) before signing with the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association in July 1950. He hit .302 in 59 games with the Brewers that season, .343 in 97 games in 1951 (when the Brewers won the American Association regular season and playoffs plus the Junior World Series), and started the 1952 season with Milwaukee.

Then in late April Clarkson got the call to join the Boston Braves. Al Hirshberg told the story in The Sporting News of May 7, 1952:

In desperation the Braves pulled James (Buzz) Clarkson up from their Milwaukee farm. Clarkson is a comparative ancient colored shortstop…The only thing against him is his age, which is indeterminable….Clarkson doesn’t exactly fit in with the Braves’ new youth movement, but he can hit and he can play short, and the Braves have got to do something to strengthen themselves.

While Clarkson was with the Braves his high school coach “confirmed” he was only 34 years old. But according to the Social Security Death Index, Clarkson was born March 13, 1915, making him 37 when he debuted in Boston. What’s funny is, according to the 1951 edition of “Who’s Who in the American Association” (source of the photo I’ve used), Clarkson would have been even older — it lists his birth date as March 3, 1913.

Clarkson got a pinch-hit single in his first major league at-bat and started three games in his first week in the majors, but when he went 1-for-10 in those games he was sent to the bench and pretty much ignored, getting just four at-bats and one start over a nearly-four-week period. Then on June 1 the Braves replaced manager Tommy Holmes with Charlie Grimm in a move that would have seemed to be good news for Clarkson, since Grimm had managed him at Milwaukee the previous season. Only in his first move, Grimm sent Clarkson back to the Brewers. He soon returned to the Braves but went 1-for-10 before being sent to the minors for good with a lifetime major league average of .200 (5-for-25).

Clarkson continued to thrive in the minors, hitting .318 with 12 homers in 74 games at Milwaukee in ’52 (the Brewers won another pennant), .330 with 18 homers for Dallas of the Texas League in 1953 (the Eagles won the TL pennant, playoffs and Dixie Series), and .324 with 42 homers in the Texas League in 1954 (he was traded from Dallas to Beaumont the previous winter and then dealt back to Dallas in June 1954). He spent two more years in the minors before ending his Organized Baseball career at age 41.

Clarkson spent a number of winters playing in Puerto Rico, and in the winter of 1954-55 he was a teammate of the above-mentioned Bob Thurman on the great team at Santurce.

From left to right: Willie Mays, Roberto Clemente, Buzz Clarkson, Bob Thurman and George Crowe. Not a bad lineup.

SABR member Nick Diunte tells more of Clarkson’s story here.

I’m really stumped on Art Jacobs, whose major league career consisted of one game when he was 36. But I confess I haven’t spent a lot of time researching him.

The distinctively-named Otho Nitcholas shares characteristics with several other players on this list: he won a lot of games (in his case, 254) in a long minor league career, and he passed himself off as younger than he was (the 1945 Street & Smith’s lists his birth date as Sept. 13, 1911, when he was actually born three years before that).

Nitcholas was in double figures in victories in each of his first 14 seasons in professional ball; that would be every year from 1932 through 1946, except for 1939, which he sat out with “a rheumatic condition which has affected his arm,” according to an Associated Press dispatch that spring. Of course, he was in double figures in losses most of those years too (he wound up with 200 career losses), but he routinely pitched more than 200 innings a season and did a creditable job.

Nitcholas went 14-11 with a 2.89 ERA for St. Paul of the American Association in 1944 and was purchased by the Dodgers for the following season. He started 1945 in Brooklyn, at age 37, and made seven relief appearances, getting one win in a six-inning stint, before being returned to St. Paul.

Nitcholas pitched in the minors until he was 43 and was a player-manager his last three seasons. He did quite well in the lower minors in his later years, going 18-7 with a league-leading 1.97 ERA in the Class C Lone Star League in 1948, 17-5 in the Class C Evangeline League in 1951, and 14-5 in the Class C West Texas-New Mexico League in 1952.

After his playing career Nitcholas went into law enforcement and was the police chief in the Dallas suburbs of Plano and McKinney (his hometown). He retired as McKinney’s chief in 1970 with health concerns after one of his patrolmen was shot to death in the line of duty.

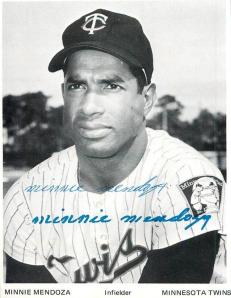

Christobal “Minnie” Mendoza was a feel-good story when he made the opening day roster of the defending American League West Division champion Minnesota Twins in 1970, after 16 seasons in the minors (12 of them with the Twins, or their predecessors, the Washington Senators). The Twins said he was 36 (using the birth date that’s still believed to be correct), but Mendoza insisted he was 34. His promotion to the big leagues wasn’t exactly a gift; the previous season he had led the Class AAA American Association with 194 hits and batted .333. “Sometimes I feel like quitting, but I don’t,” he said in the spring of 1970. “I love baseball. I love to travel, too.”

Christobal “Minnie” Mendoza was a feel-good story when he made the opening day roster of the defending American League West Division champion Minnesota Twins in 1970, after 16 seasons in the minors (12 of them with the Twins, or their predecessors, the Washington Senators). The Twins said he was 36 (using the birth date that’s still believed to be correct), but Mendoza insisted he was 34. His promotion to the big leagues wasn’t exactly a gift; the previous season he had led the Class AAA American Association with 194 hits and batted .333. “Sometimes I feel like quitting, but I don’t,” he said in the spring of 1970. “I love baseball. I love to travel, too.”

But it turned out there was no role for Mendoza to play with the Twins. He got into only 16 games, with no starts, and had three singles in 16 at-bats before being sent back to the minors in mid-June. And he won another batting title in the minors, hitting .316 to lead the Class AA Southern Association in 1971, when he was 37, helping the Charlotte Hornets win the pennant. (He played in Charlotte for 10 seasons and was enormously popular there.) Mendoza finished his minor league career with 2,502 hits (his record on Baseball-Reference.com does not include the 43 hits he got in the Mexican League in 1973).

Another Twins player who debuted at age 36 (and one who, like Mendoza, was also a native of Cuba) was Enrique “Hank” Izquierdo, who had actually retired as a player five years before he finally made the big leagues in 1967. In four seasons with Cincinnati’s Class AAA teams from 1957-60 Izquierdo posted batting averages of .153, .196, .218 and .186. Not exactly encouraging. In 1961 he was a player-coach with the Reds’ AAA team at Jersey City, and in 1962 he stopped playing altogether to be a bullpen catcher for the Cleveland Indians.

Another Twins player who debuted at age 36 (and one who, like Mendoza, was also a native of Cuba) was Enrique “Hank” Izquierdo, who had actually retired as a player five years before he finally made the big leagues in 1967. In four seasons with Cincinnati’s Class AAA teams from 1957-60 Izquierdo posted batting averages of .153, .196, .218 and .186. Not exactly encouraging. In 1961 he was a player-coach with the Reds’ AAA team at Jersey City, and in 1962 he stopped playing altogether to be a bullpen catcher for the Cleveland Indians.

But he missed playing, so in 1963 Izquierdo hooked up with the Twins and dropped down to the Class A Florida State League, where he hit .297 and rekindled his career. By 1966 he was back up to AAA, and in ’67 he hit .300 for Denver of the Pacific Coast League to earn another call to the big leagues — this time as part of the active roster, when Earl Battey went on the disabled list with a dislocated thumb. It didn’t hurt that Cal Ermer had replaced Sam Mele as the Twins’ manager; Ermer had started the season at Denver and had also managed Izquierdo in winter ball.

With the Twins in the thick of one of the greatest pennant races in history (they wouldn’t be eliminated until the last day of the season), Izquierdo did just fine when called upon. The Twins went 7-2 in the games he started, and he finished the season with seven hits in 26 at-bats for a .269 batting average.

After the season Izquierdo was drafted by the Houston Astros’ Oklahoma City farm club and spent two years with them. After the 1968 season he was nearly killed while driving a cab in Miami when he was shot during a robbery, then his 1969 season ended prematurely when he was suspended for the rest of the season by American Association president Allie Reynolds after swinging a bat at future major league star Ted Simmons during an on-field argument. Izquierdo went on to manage in Mexico before returning to the Twins as a scout.

I wrote the story of Ernie Rudolph a few years ago. When Ernie broke in with the Brooklyn Dodgers at age 36, he became the first — and only — man ever to make it from Class E to the major leagues. You didn’t know there was a Class E? Go back to the beginning of the paragraph and click that link.

Joe Vitelli had not pitched professionally since 1940 when Pittsburgh Pirates manager Frankie Frisch hired him as a batting practice pitcher early in the 1944 season. (And yes, Vitelli may have altered his age; the 1945 Street & Smith’s lists his birth date as April 25, 1911, when it was actually April 12, 1908. At any rate, this item announcing his signing said he was 36, which was correct.) Frisch had only seven men on his pitching staff, one of whom had a sore arm, and in those days the team’s regular pitchers usually threw batting practice. Vitelli pitched in four games during the season, all of them blowout losses, and was voted a full $722.48 share of the World Series receipts the Pirates received for finishing second in the National League.

Vitelli continued to pitch batting practice but got into just one game in 1945 — and as a pinch-runner, at that — and left the team in midseason “in a dissatisfied state of mind,” according to a story in The Sporting News of July 12, 1945. Charles J. Doyle wrote Vitelli “thought he should have been given a chance to pitch, so that he could earn more money.” I don’t know what kind of contract Vitelli was on that has pay would be dependent on his pitching appearances.

A former football player at the University of Pittsburgh who also played semi-pro football, Vitelli started his pro baseball career in 1932. He spent the 1936 season playing semi-pro ball in the Pittsburgh area after a dispute with his team, Norfolk of the Class B Piedmont League, according to a story in The Sporting News of July 22, 1937. (That story lists his birth date as April 12, 1912.) He returned to pro ball in 1937 and posted a 17-10 record with Albany of the Class A New York-Pennsylvania League, finishing second in the league’s most valuable player voting (behind future major leaguer Jim Bagby, Jr.) despite pitching for a last-place team. The highlight of the season was when he pitched an 18-inning complete game against Binghamton, striking out 20 and driving in the winning run. But he complained of a sore arm in 1938 and never got beyond the Class A level before joining the Pirates in 1944.

I’m sure there’s a really interesting story to tell about Vitelli, but I haven’t found much of it. You’ll find a little more here. (ADDED 8/13/18: And there’s more about Vitelli in this profile in the SABR BioProject.)

Buck Fausett (apparently one of his other nicknames was “Leaky”) was another longtime minor league star who got a chance to play in the majors during World War II. And yes, he’s another one who fudged his age, at least during his younger days; The American Association On Parade 1936 lists his birth date as April 8, 1911, when he was actually born three years earlier. But stories in The Sporting News when he was with the Reds in 1944 have his age as 36, which was correct.

A graduate of East Texas State Teachers College (now known as Texas A&M University-Commerce), Buck was a third baseman in the Texas League from 1932-35. He went to spring training with the Philadelphia A’s in 1935…here’s how he told the story in 1944:

Two days before training camp broke, I squabbled with [A’s owner/manager Connie] Mack over money. I was sent back to Galveston. Mack had Pinky Higgins playing third at the time. I knew I didn’t have a chance to beat him out. On the second day of the season, Higgins broke his leg. If I had been on the spot, my major league career would have started then.

Fausett told the story in more detail in The Sporting News of April 27, 1944. Mack had purchased both Fausett and Galveston teammate Wally Moses on a conditional basis, and he had decided to keep them. But Fausett balked, saying the owner of the Galveston team also gave him an offseason job that brought his total income to more than what the A’s would pay him, and he wouldn’t be able to have that winter job if he were no longer playing for Galveston. So under the circumstances (there was a Depression going on, after all), Fausett told Mack he preferred to go back to Galveston.

Fausett would not get a second chance to make the majors in the ’30s. He played in the American Association from 1936-41. After a poor year at the bat with Minneapolis in ’41 (a season in which he also took to the mound for the first time, pitching 14 games and starting seven), Fausett went to Little Rock in 1942 and helped his team win the Southern Association pennant, batting .334. The next year he became the team’s manager and finished second in the league in batting average with a .362 mark (he also pitched four games). At the end of the season the Cincinnati Reds purchased his contract. (It was reported Fausett’s draft status was 3-A.)

Part of a graphic that appeared with a story about Buck Fausett in The Sporting News of April 27, 1944

The Reds didn’t have much of a spring training in 1944 for manager Bill McKechnie to sort out his third base situation, so the position was still up in the air as the regular season began. Returning starter Steve Mesner was in the lineup the first three games; Chuck Aleno, who had been with the Reds in previous seasons, started the next four. And then Fausett got his chance, starting the next six games. It didn’t go well, as he got just two hits in 22 at-bats, and he never played third in the majors again.

His last two major league appearances were as a pitcher. On June 1 he pinch-hit and pitched four innings of relief at Philadelphia, allowing two runs. His final appearance came in a game that remains famous today, on June 10 at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. With the Reds trailing 7-0 and only one out in the second inning, McKechnie put Fausett on the hill to take one for the team, and Buck pitched 6-2/3 innings, allowing six runs. The reason the game is famous is the pitcher who relieved Fausett in the ninth inning: Joe Nuxhall, who at age 15 became — and remains — the youngest player ever to appear in a major league game.

Fausett did get a hit in that final game to raise his career major league batting average to .097 (3-for-31).

Shortly thereafter Fausett was sold to Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League, where he went back to being a quality minor league player. He also managed the Stars in 1945 and part of 1946 before he was sent to Albuquerque of the Class C West Texas-New Mexico League.

The high altitudes and lower quality competition of that league allowed Fausett to record monster seasons in his final two years as a player, when he was 39 and 40 years old (he managed those years as well). In 1947 he hit .409 with a career high 20 homers, 142 RBI and a league-leading 21 triples for Albuquerque; then in 1948 he hit .398 and knocked in 101 runs in 109 games for Amarillo. Fausett finished his minor league career with 2,679 hits (not showing on his Baseball-Reference.com page are two hits he got as a player/manager at Amarillo in 1949). (ADDED 9/9/16: I’ve written a more complete biography of Fausett for the SABR Bio Project.)

Two players who came up when I did this search on Baseball-Reference.com’s Play Index turned out to be younger than they are listed, so I have not included them in the lists below. Bill McGhee, who broke in with the 1944 A’s, was born in 1908, not 1905, so he was 35 when he debuted. And Dutch Stryker of the 1924 Braves was born in 1895, not 1885. Also, please note Baseball-Reference.com has not updated Billy Williams’ birth date…his age should be 37 years and 63 days.

With those exclusions, here are the non-pitchers since 1916 who were 36 or older when they played their first major league game. Click the name to see the player’s lifetime stats, and click the date to see the box score of his first game. Note none of these players started in his first big league game.

| Player | Age | Date | Tm | Opp | Rslt | PA | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | Pos Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chuck Hostetler | 40.210 | 1944-04-19 | DET | SLB | L 1-3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PH |

| Quincy Trouppe | 39.127 | 1952-04-30 | CLE | PHA | L 1-3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C |

| Bob Thurman | 37.335 | 1955-04-14 | CIN | CHC | L 4-6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PH |

| Lee Riley | 37.243 | 1944-04-19 | PHI | BRO | L 4-5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PH |

| Buzz Clarkson | 37.048 | 1952-04-30 | BSN | PIT | L 5-11 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PH SS |

| Minnie Mendoza | 36.144 | 1970-04-09 | MIN | CHW | W 6-4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3B |

| Hank Izquierdo | 36.142 | 1967-08-09 | MIN | WSA | L 7-9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PH C |

| Billy Williams | 36.063 | 1969-08-15 | SEP | BAL | L 1-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PR |

| Buck Fausett | 36.010 | 1944-04-18 | CIN | CHC | L 0-3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PH |

And now the oldest pitchers to make their major league debut. Scantlebury is the only one who started.

| Player | Age | Date | Tm | Opp | Rslt | IP | H | R | ER | BB | SO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satchel Paige | 42.002 | 1948-07-09 | CLE | SLB | L 3-5 | 2.0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Diomedes Olivo | 41.227 | 1960-09-05 (2) | PIT | MLN | L 1-7 | 2.0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Ken Takahashi | 40.016 | 2009-05-02 | NYM | PHI | L 5-6 | 2.2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Alex McColl | 39.151 | 1933-08-27 (2) | WSH | CLE | L 3-6 | 3.1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Les Willis | 39.101 | 1947-04-28 | CLE | DET | L 0-3 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Masumi Kuwata | 39.070 | 2007-06-10 | PIT | NYY | L 6-13 | 2.0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Connie Marrero | 38.361 | 1950-04-21 | WSH | NYY | L 7-14 | 0.2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pat Scantlebury | 38.160 | 1956-04-19 | CIN | STL | W 10-9 | 5.0 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Joe Berry | 37.264 | 1942-09-06 (2) | CHC | PIT | L 0-5 | 1.0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Joe Strong | 37.245 | 2000-05-11 | FLA | ATL | W 5-4 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chang-Yong Lim | 37.095 | 2013-09-07 | CHC | MIL | L 3-5 | 0.2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Art Jacobs | 36.294 | 1939-06-18 (1) | CIN | BSN | W 12-6 | 1.0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Otho Nitcholas | 36.217 | 1945-04-18 | BRO | PHI | L 2-6 | 2.0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Satoru Komiyama | 36.201 | 2002-04-04 | NYM | PIT | L 2-3 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Keiichi Yabu | 36.193 | 2005-04-09 | OAK | TBD | L 2-11 | 3.2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Ernie Rudolph | 36.123 | 1945-06-16 | BRO | BSN | L 5-6 | 2.2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Takashi Saito | 36.054 | 2006-04-09 (1) | LAD | PHI | L 3-6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Joe Vitelli | 36.039 | 1944-05-21 (2) | PIT | PHI | L 4-9 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Aside from Scantlebury, the next oldest pitcher to start in his major league debut was Jesse “Andy” Rush, who was 35 years and 111 days old when he debuted for Brooklyn in 1925. Here are the oldest players to start in their first big league game at each of the other positions:

| C | Earle Brucker | 1937 A’s | 35.348 |

| 1B | Bill McGhee | 1944 A’s | 35.304 |

| 2B | Johnny Butler | 1926 Dodgers | 33.029 |

| SS | Louis Brower | 1931 Tigers | 30.347 |

| 3B | Lew Groh | 1919 A’s | 35.290 |

| LF | Dick Spalding | 1927 Phillies | 33.187 |

| CF | Ty Tyson | 1926 Giants | 33.316 |

| RF | Jocko Conlan | 1934 White Sox | 34.212 |

| DH | Alejandro Friere | 2005 Orioles | 30.351 |

Lew Groh, who played in only two major league games, was the older brother of deadball era star Heinie Groh. Jocko Conlan went on to make the Hall of Fame as an umpire.

Thanks for linking my story on Clarkson. I think in this article, you mean Minnie Mendoza, not Minoso.

Doh! Yeah, how many times can a guy proofread and still miss that? Correction made–thanks, Nick.

BRJ-worthy! Great stuff ~ There’s probably an intriguing scouting story that can go along with each of these guys…

Cool post, but it needs a small correction: Chang-Yong Lim is from Korea, not Japan.

Well, he last played in Japan before the majors, is what I meant.

Pingback: Forget Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak: Billy Parker has a baseball record that will NEVER be broken | The J.G. Preston Experience

I’m the son of Pat Scantlebury and I enjoyed reading your tidbit on some of the oldest rookies.

Thank you, Terence…if there’s anything I should add about your father please let me know!

I will do that. Again it was interesting.

Pingback: The 1970 Twins and APBA lead to a discovery… | Vintage Twins

Porfirio Altamirano a right hand pitcher from Nicaragua was 32 Years old when he was call up to the mayor league to play with the Philadelphia Phillies.